By Bernat Olle, PureTech Ventures

By Bernat Olle, PureTech Ventures

Does it have to be a biotech or pharma company that figures out a way to monetize fecal transplants (FTs)? Or will hospitals find a way to make them appealing to patients without help from industry?

Given the potential hurdles involved, many in the popular press have questioned whether FT can be successfully commercialized (me too). Regardless, people will try to find a way. They will need to come up with a viable business model and navigate numerous challenges.

Commercializing Fecal Transplantation: Who Can Stomach the Challenges?

Let me skip the background on FT (I've written about it in this previous entry) and get right to the topic of commercialization. A number of challenges stand in the way of commercializing FT. Some have already been discussed at length in the press, such as patient and physician perceptions of the procedure (the "ick factor"). Others have gotten little attention, such as the inability to get broad IP protection on the approach and uncertainty around the regulatory route that will apply to FT. And some have gotten no attention at all, such as manufacturing challenges, the lack of a proven business model and challenges around reimbursement.

Patient perceptions: The really desperate patients have bigger worries than the "ick factor"

The visceral distaste the general population has for the procedure may not necessarily change with new data from well-controlled, randomized trials of FT. However, the views of the general population are not necessarily representative of how patients with Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) at the end of the rope feel about the procedure (think patients who repeatedly relapse or experience the fulminant form of the disease, for whom the alternative can be emergent resection of the colon). This topic has been covered at length by others (see for example Maryn McKenna's story in Scientific American), so I won't elaborate here.

Intellectual Property: Little room to get broad patents

There are decades of prior art that would preempt broad claims around pharmaceutical compositions consisting essentially of feces and around the FT procedure. Going into this in depth deserves a whole separate piece. Suffice it to say that the basic steps of obtaining a sample from a prescreened donor, FT preparation (use of preservatives like saline, homogenization, filtration), recipient preparation (lavage, pretreatment with antibiotics), and means of administration (nasogastric and nasoduodenal tubes, colonoscope, or retention enema) have been described in the art and are off the table. Novel methods to select donors or improvements on methods to process and administer samples could well be patentable, but I am not convinced these would clear the bar for IP protection that Pharma expects. (Specific compositions of well-characterized microbial consortia will likely be more attractive to Pharma; more on them in a future entry.)

Uncertainty on which regulatory framework will apply

Will FTs be regulated as biologic drugs, human cell and tissue products (HCT/Ps), medical procedures or none of the above? In principle, FTs meet the FDA's definition of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs): a biological product that: 1) contains live microorganisms, such as bacteria or yeast; 2) is applicable to the prevention, treatment or cure of a disease or condition of human beings; and 3) is not a vaccine. However, meeting the FDA's GMP standards for LBPs would be unworkable for an FT product, which can contain thousands of bacterial species. Characterizing each of the strains in a FT to GMP standards and with all the reproducibility, validation and documentation required is out of the question. Not only is it technically unfeasible, but nobody would be able to afford the cost of an FT produced by these standards.

Alternatively, the current regulatory framework for HCT/Ps could provide some guidance. Cell therapies pose challenges to the traditional Investigational New Drug Application (IND) or Biologics License Application (BLA), U.S. regulatory approval pathways similar to those that FT can expect to encounter (donor eligibility, tests for infectious agents, manufacturing requirements, regulation on manipulations that might alter the biologic function of the composition, storage and distribution protocols, etc.). An obvious difference is that an FT is composed of microbial rather than human cells (although what should and should not be considered "human" in light of the evolving understanding of humans as "superorganisms" has philosophical undertones best left to others to debate). Either way, the FDA's Tissue Reference Group apparently has recommended against regulating FTs as HCT/Ps ("Microbiota isolated from fecal matter of a donor is not an HCT/P, as defined under 21 CPR 1271.3(d)"). So scratch HCT/Ps.

FTs also share attributes with medical procedures such as bone marrow transplants, human organ transplants, blood transfusions and transfusions of blood-derived products. By way of an analogy, reconstituting the gut microbiota via a fecal transplant can be considered akin to reconstituting the hematopoietic system via hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). There are some nontrivial differences between the two that in my view make HSCT a far more dangerous and complex procedure: Immunological matching will probably not be required for FT, which substantially expands the pool of donors; conditioning regimens are much simpler for FT than for HSCT, which usually requires the recipient's immune system to be destroyed with chemo or radiation; and fatal complications, e.g., graft-versus-host disease in HSCT, are unheard of for FT. Blood transfusion procedures are also loosely analogous to FT. Donor screening protocols (health history, presence of infectious agents, etc.) are comparable, with the notable exception, again, that FTs don't require immunological matching. The composition of blood transfusions for different individuals cannot be standardized; neither can that of FTs. Different blood groups occur, and it has been proposed that different microbiome types may occur in the human population too, although this remains a very controversial topic among academics in the field.

I think it is conceivable that the FDA would allow hospitals to offer FT as a medical procedure. This could be rationalized on the basis that FT manufacturing involves minimal manipulation of donor samples and that a fecal transplant directly replaces the function for which it was biologically intended (the transplant "repopulates" a recipient's previously damaged microbiota). Under this scenario, FTs would not be considered commercial products, would be overseen instead by state Medical Boards, and would face less regulatory scrutiny than LBPs or HCT/Ps. I doubt, however, that the FDA would let companies commercialize FTs as medical procedures. Unless all the operations of preparing a FT are conducted at the hospital and in a short period of time, it is difficult to claim that the FT has not been manipulated and its stability has not changed. Any step such as freezing, thawing, preparation of a defined dose, packaging, storage, or shipping could be seen as a manipulation. If the experience with processed blood products and cell therapies is of any guidance, the FDA might sooner or later designate companies manufacturing FTs as biological drug manufacturers and require from them a BLA. An illustrative example of an FDA-approved blood product for which manufacturers are required to get a BLA is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Among other things, IVIG manufacturers are asked to specify any additives and modifications made to the final product, guarantee the product is free from certain harmful contaminants, and have in place suitable quality-control release tests. Similar requirements could be demanded from FT products.

It will be interesting to see what balance the FDA strikes between safety and encouraging translation of FTs. As far as I am aware, the agency hasn't really made its thinking known, but it could do a good service to this field by emphasizing safety standards over product testing standards, since there are some serious questions over the ability of existing technologies to ensure product consistency and quality of FTs.

Plausible Business Models: Individualized vs. Off-the-Shelf Treatments

Potential business models for commercializing FT may involve hospital medical procedures, commercial products and services, or a combination of both.

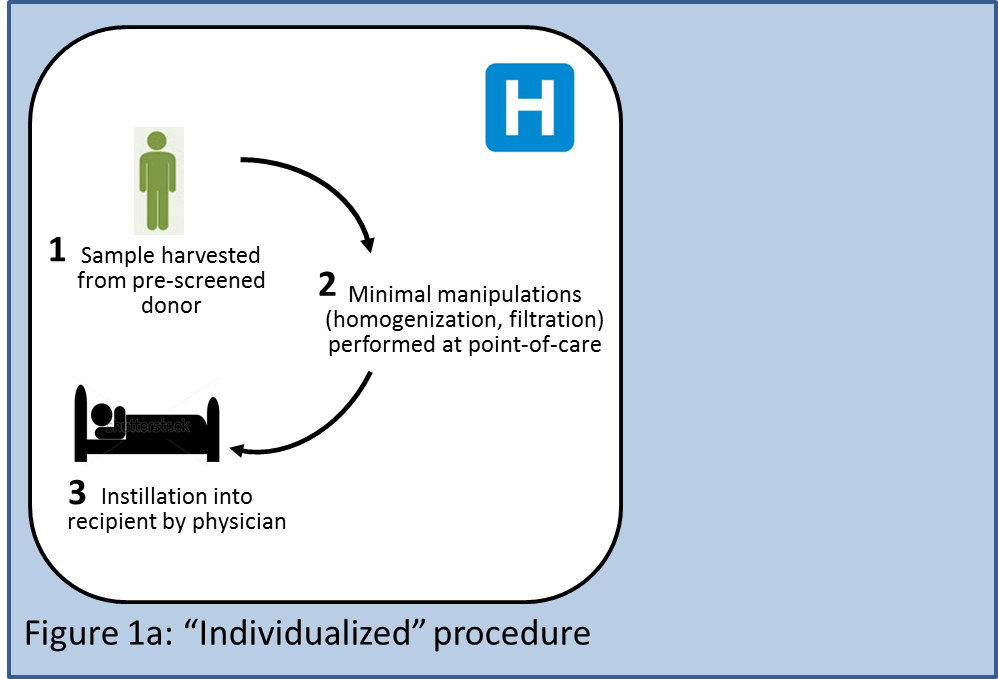

Two potential business models would be individualized and off-the-shelf approaches, both of which are currently being pursued for stem cell transplants. An individualized procedure (Figure 1a) could be performed entirely at the hospital or transplant center: A stool sample would be obtained from a prescreened donor; the sample would be minimally manipulated (homogenization, filtration); and finally, a physician would take the fresh sample and instill it into a recipient. The sample would never leave the premises of the hospital, which would minimize the time delay between harvest and instillation. Hospitals could potentially generate revenue streams from testing donors, from labor involved in collecting the stool sample, processing it, and instilling it, and from monitoring and testing the recipient (not all of these procedures may be reimbursed, though; see section below). Disposables such as lavage solutions or nasogastric tubes could be sold individually or as kits, and would generate revenue for existing suppliers of these products. This model could face the lowest regulatory hurdles assuming hospitals were allowed to offer FT as a medical procedure exempt of regulatory approval. Variability of the results due to donor heterogeneity and nonuniform processes across hospitals could be a potential concern.

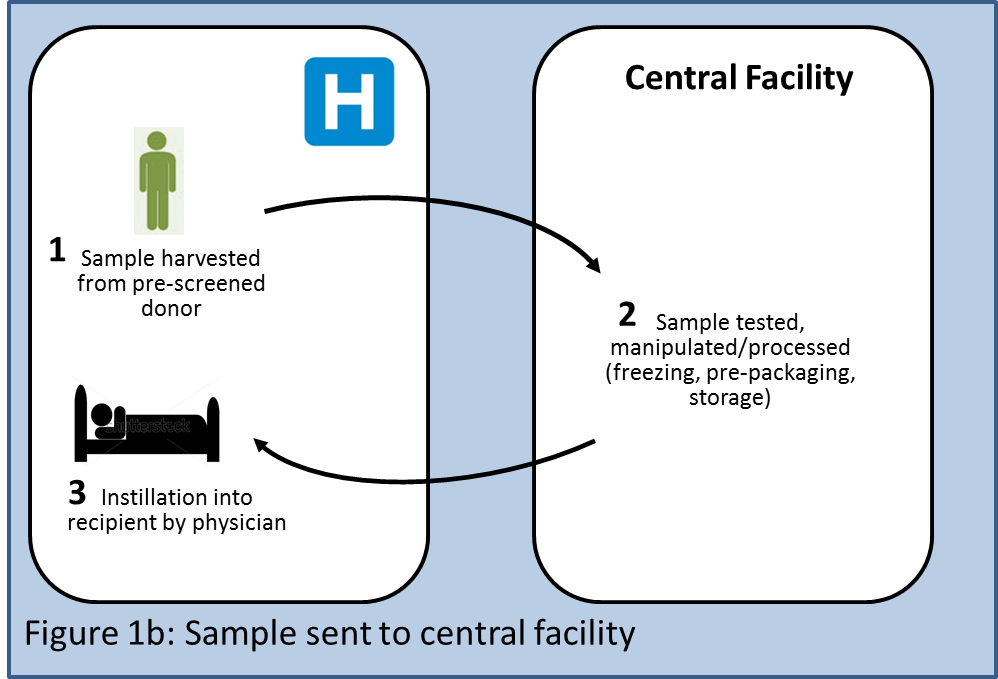

A first variant of this individualized model would involve donor stool samples being sent to a central facility (Figure 1b) which could do all the necessary testing, process the samples, freeze them, optionally prepackage them into an application device such as a colonoscope, and store them. Any such additional steps would likely invite stricter regulatory oversight. The product would be shipped to the physician, who would instill it into the recipient. This alternative would enable performing more complex manipulations of the sample offsite (e.g., increasing quantities of certain microbes within the sample, reducing quantities of other microbes with antibiotics, etc.), although at present there is no science that indicates that such manipulations would be desirable. Each donor sample would be processed as an individual batch, requiring individual acceptance testing to determine the quality of the raw materials, in-process testing, and release testing to establish the quality of the final product. Downsides of this model would include stricter regulatory oversight, higher cost of goods, introduction of a time delay between harvesting and instillation, and more complex logistics.

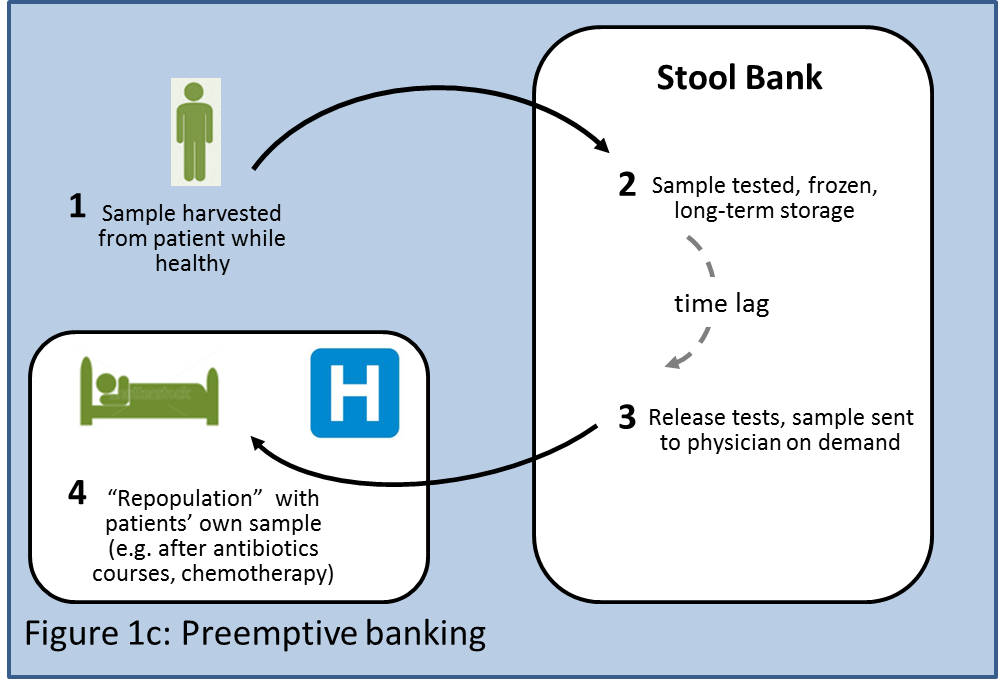

A second variant of the individualized model could involve preemptive banking (Figure 1c) of a patient's stool for use in the future by the same patient (akin to umbilical cord blood banking). Patients could send stool samples for banking in a central facility while they are healthy. The banked samples would be available to "repopulate" the patient if in the future he needs to undergo aggressive antibiotic courses or chemotherapy that might damage his microbiota.

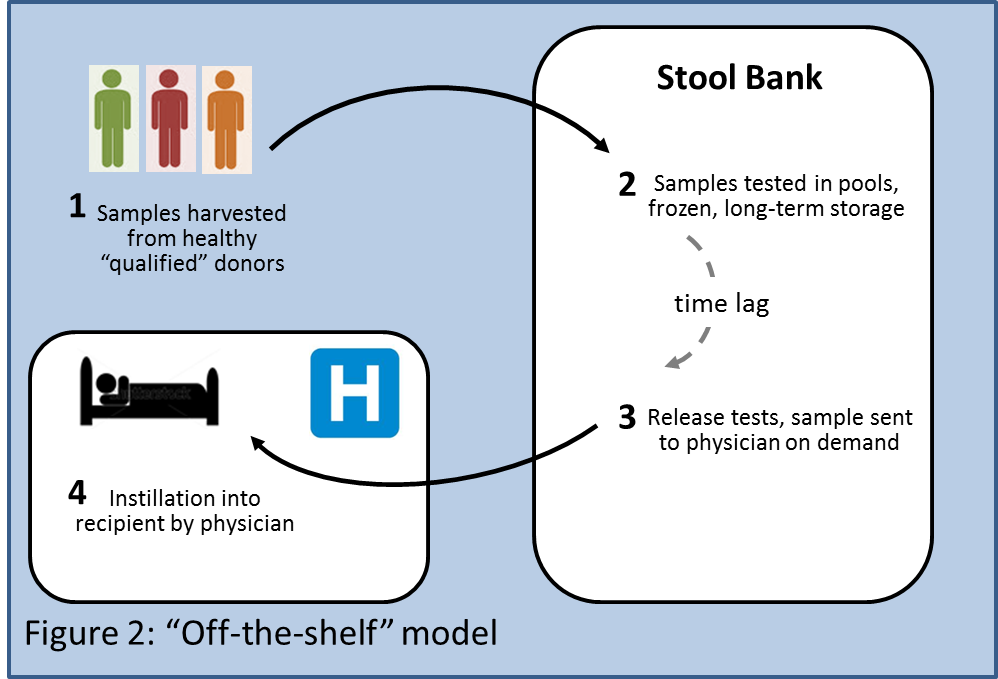

An "Off-the-Shelf" business model (Figure 2) could involve obtaining samples from a limited number of "qualified" donors. These subjects would be prescreened with standardized tests, and their stool samples would be processed and banked in a central facility, and later shipped on demand when requested by a physician. There would be an additional cost for maintaining the stool bank, but that could be offset by lower cost of goods of the product since each donor could provide several batches, which could be screened as one pool, resulting in less frequent acceptance, in-process, and release testing. As in 1b and 1c, manipulation steps such as freezing, storage or addition of agents could also attract stricter regulatory oversight.

The viability of each of these models hinges on the regulatory framework applied to them and on how FT gets reimbursed in the future. The uncertainty is likely to keep many on the fence, but biotech startups with an appetite for risk may take the challenge. There is evidence that this is already the case, since a couple of startups have entered the FT stage (some info on them here).

Reimbursing FT: Are We Turning a Corner?

The economic burden of CDI is huge and growing. According to the CDC, 14,000 deaths each year in the U.S. are linked to CDI, and it costs on the order of $1 billion annually to treat infections. The rate of infections is at an all-time high, and the emergence of a hypervirulent strain has contributed to a 400% increase in deaths between 2000 and 2007. The numbers are just plain scary.

The current standard of care is oral administration of antibiotics such as vancomycin and metronidazole, which cost on average ~$400 per episode (but can cost up to three times as much). However, the biggest burden to the healthcare system comes from associated inpatient care costs, which are on average $11,000 per episode. Payers ought to be thinking seriously about the prospect of a curative treatment that could take a chunk of these patients out of the healthcare system in one shot.

The lack of reimbursement for FT has been pointed to as a factor impeding broader use of the procedure. Until recently, physicians performing FT could get reimbursed only for the colonoscopy procedure (if that was the method of instillation used), but not for donor and patient pretesting (e.g., testing donor for Hep A, B, and C, HIV, parasites, etc.), which can cost several hundred dollars, or for the labor in preparing the sample. A recent development indicates that attitudes toward reimbursement are evolving, though. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have just created a new code for CY2013 for FT (HCPCS Code G0455) which covers the work of preparation and instillation of the microbiota by any method. This is a first step. It is still unclear if any of the necessary donor and patient pretesting will be covered. The pretesting is not cheap, but it would make economic sense for payers to cover it considering the potential savings in pharmacy and inpatient care costs versus the current standard of care.

The recent randomized, controlled study of FT published in NEJM brings a new argument to this discussion. It shows modification of disease progression and restoration of normal physiological function for CDI, not just short-term relief. It may help make a strong case to payers to cover the procedure more generously. If they don't, hospitals may want to pick up the tab: Most CDI cases originate in the hospital setting, where unnecessary antibiotic use contributes to the problem. The germs spread with patients and providers across healthcare facilities. Perhaps a warning sign of more rules to come, in 2013, acute care hospitals will have to start reporting CDI cases to CDC.

Where to from here?

In its current form, FT may not attract the attention of pharmaceutical companies, which are more likely to focus on second-generation products (e.g., well-defined and characterized cocktails of strains). However, standardization of the FT procedure, rigorous donor screening, and more comprehensive reimbursement could enable hospitals to broaden its appeal among physicians and patients. That is, of course, assuming regulators allow it.

Dr. Bernat Olle is a principal at PureTech Ventures. He has been a member of the founding teams of Follica, Vedanta Biosciences and Enlight Biosciences. He serves as the chief operating officer and a member of the board of directors of Vedanta Biosciences. He completed his doctoral work at the Chemical Engineering Department at MIT, where he co-developed a novel method to increase oxygen transfer in bioreactors by using colloidal nanoparticles.

Other contributions from Bernat Olle:

Industry Voices: Time to Take Fecal Transplantation Seriously

Industry Voices: Designing Probiotics - You Get What You Select For

Industry Voices: Microbiome Therapies - Coming to a Clinic Near You