|

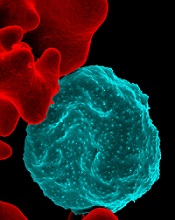

| Red blood cell infected with malaria parasites (blue)--Courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases |

In a discovery that could put a vaccine for malaria closer in sight, scientists have linked an antigen to an essential function in malaria-causing parasites that enables them to escape from inside red blood cells and infect the rest of the body.

"Many researchers are trying to find ways to develop a malaria vaccine by preventing the parasite from entering the red blood cell, and here we found a way to block it from leaving the cell once it has entered," Dr. Jonathan Kurtis, director of the Center for International Health Research at Rhode Island Hospital, said in a statement.

Trapped in the red blood cell, the parasite has nowhere else to go and can't cause any further damage, Kurtis explained. Kurtis and his team found that antibodies generated by this antigen, called Schizont Egress Antigen-1 (PfSEA-1), trap the parasite inside these red blood cells.

Researchers vaccinated 5 groups of mice that had been exposed to malaria with the PfSEA-1 antigen. In every group, vaccinated mice had lower levels of malaria parasites and survived longer than unvaccinated mice. The research was published in the journal Science.

The researchers then measured antibodies to PfSEA-1 in a Tanzanian birth cohort of 785 children, and found that among children with antibodies to PfSEA-1, there were no cases of severe malaria. To further test their results, the scientists examined serum collected from 140 children in Kenya in 1997. They found that individuals with antibodies to PfSEA-1 had 50% fewer parasites than individuals without these antibodies during a season of high transmission.

Kurtis and his team plan to test the vaccine in another animal model and initiate a Phase I trial after that.

- see the study abstract

- read the press release