Inflammation can clear the body of invading microbes or particles, but too much of a good thing can leave a person in septic shock, with multi-organ failure or dead. Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified in a mouse study the body's molecular "brake" that keeps inflammation in check, which could have implications in age-related diseases.

|

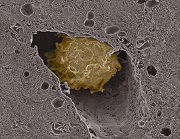

| Macrophage in the liver--Courtesy of UC San Diego |

Macrophages, a type of white blood cell, play a major role in inflammation. They engulf invading microbes and release cytokines, proteins that act as signals to recruit and activate other immune cells. Macrophages' inflammasomes produce cytokines, but in the case of interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta), foreign particles don't directly cause inflammasomes to react.

Instead, particles like silica and asbestos damage the macrophages' mitochondria, which in turn release signals activating the inflammasome responsible for producing IL-1beta, wrote UC San Diego's Heather Buschman in a statement.

While responding to foreign particles, macrophages also ramp up production of a protein called p62, the molecular "brake." P62 coats damaged mitochondria, ensuring that they are eliminated and resulting in the deactivation of the IL-1beta-producing inflammasomes.

"We've suspected for quite some time that damage to mitochondria caused by either genetic or environmental factors is the root cause of many age-related diseases, all of which are associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation," said Zhenyu Zhong, a postdoctoral researcher who led the study with Michael Karin, a pharmacology and pathology professor at UC San Diego.

"Therefore, p62--and its part in eliminating damaged mitochondria--could provide a new target for preventing such diseases. Indeed, we already know that another protein that collaborates with p62 to eliminate damaged mitochondria is Parkin, which plays a role in a rare form of Parkinson's disease," Zhong said.

This isn't the first time researchers have linked mitochondria to aging and age-related diseases. In February, a Newcastle University-led team proved that mitochondria trigger cell aging.

- read the release