|

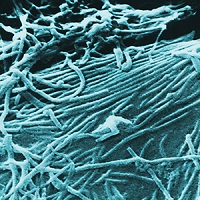

| Ebola virus particles--Courtesy of CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith |

Even as the Ebola crisis continues in Africa, little is known about the extremely fatal disease, as evidenced by the few experimental treatments in development.

But new research by scientists at Washington University in St. Louis, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center may shed some light on how the Ebola virus ravages the immune system and point to ways to stop the disease in its tracks.

In the journal Cell Host & Microbe, the team reveals a mechanism unique to the Ebola virus that thwarts efforts by protective proteins in the body--called interferons--to block the virus from replicating in infected cells.

"These newfound details of Ebola biology are already serving as the foundation of a new drug development effort, albeit in its earliest stages," said Dr. Christopher Basler, a professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and an author of the paper. Basler is also principal investigator of an NIH-funded Center of Excellence for Translational Research focused on developing drugs to treat Ebola virus infections.

Interferons are one of the human body's first responses to viral infections. When a pathogen enters the body, the host cells generate and release these signaling proteins, or interferons, which facilitate communication between cells and the immune system to coordinate an attack against the invader.

To survive, many viruses over time have evolved to undermine the immune-signaling job of interferon. The new study shows just how the Ebola virus does that.

Investigators discovered that a protein called Ebola viral protein 24 (eVP24) stops the interferon from sending signals to boost immune defenses, essentially rendering the immune system useless. Once the immune system is disabled, the virus is free to replicate and amplify within its host.

In order to be effective and fast-acting against an incoming viral infection, interferons must pass on their signal to other cells--a process that happens through other messengers inside cells as part of interferon signaling pathways. The last of these messengers activate genes inside the nuclei of cells to drive the immune response.

The researchers suggest that studying the interferon pathway further could help guide Ebola drug research. Interferon-based therapies have long been used to treat hepatitis C, but these drugs come with a host of severe side effects.

"We feel the urgency of the present situation, but still must do the careful research to ensure that any early drug candidates against the Ebola virus are proven to be safe, effective and ready for use in future outbreaks," Basler said in a statement.

- see the study abstract

- get more from Washington University

- read the press release from Mount Sinai Hospital