|

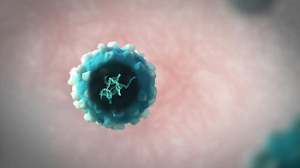

| A vector containing the correct copy of a gene--Courtesy of GSK |

GlaxoSmithKline ($GSK) and its Italian research partners are plotting major new European research hubs with future growth in gene therapies and beyond after the CHMP recommended its new "bubble boy" drug for approval in Europe on Friday.

Strimvelis (formerly known as GSK2696273) is the result of partnership between GSK and Italy's San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy and the Milanese biotech MolMed, which is based at the Institute. A deal between the groups was struck back in 2010.

The treatment is an ex vivo gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID), and is the second gene therapy to ever be approved in Europe after the 2012 green light for the Glybera, uniQure's ($QURE) $1 million lipoprotein lipase deficiency treatment.

ADA-SCID is typically dubbed as "bubble boy syndrome" as children with the disorder must be kept protected from any infections. Strimvelis works by using a virus to insert copies of the ADA gene into stem cells extracted from the bone marrow of patients. The cells are then reintroduced to the patient, who can expect to start making the gene on their own, repairing their immune system.

It had been in trials for 13 years and the CHMP recommendation--which should lead to a final European Commission approval in three months--is the start of a whole new area for the company and the Institute.

Fiona McMillan, head of specialty franchise, rare diseases and established product portfolio communications for GSK, told FierceBiotech that this is the cutting edge of truly personalized medicine.

"The drug is not so much manufactured as it is "created" for each individual patient, so we can't actually create the drug before we know there is a patient for it. But we are hoping to "launch"--though perhaps that isn't the right word for this drug--as soon as we have approval [from the EC].

"Our clinical trials closed a while ago but we have been treating patients on a named basis, so this really is the very definition of personalized medicine, and we're very excited about it."

MoIMed is currently the only approved site in the world for this type of manufacture and thus the only place where patients can be treated--but McMillan says that it won't stay in isolation for long.

"The shelf-life of the corrected cells is currently very short so they need to be infused back into the patient within a 6-hour timeframe. This requires the treatment centre to be located near to an approved cell processing laboratory, the only one of which is currently in Milan. In the much longer-term, our goal is for us to identify more sites like our Italian hub, and we're looking at a number of ways of doing that including the possibility of being able to freeze the cells which will extend the shelf-life and mean that the cells could be transported over a longer distance, potentially enabling the patient to receive the treatment at an expert hospital nearer their home location."

She said that if you start with one of the very pure targets--so in this case, ADA-SCID--you get into a rare disease and thus an individual gene that is the cause of a problem. This in turn gives a unique window into an aspect of human biology that the drugmaker can then take significant learnings from and apply that to other conditions for the longer term.

"So the hope is that what we can find out from this first indication and future indications [which will also be ultra-orphan designations] will be able to be applied to more prevalent diseases," she said.

"It's all very early stage, but that's the kind of innovation we want to produce from this initial recommendation."

There are currently only around 15 cases of the disorder across Europe each year, with an estimated 350 patients worldwide. McMillan said the priority had been getting the European approval, but added that the drugmaker would also seek FDA approval and that GSK are looking at what the next steps for that will be, given that it has different demands for clinical trial data than the EMA.

It will hope to have better luck than uniQure, which late last year abandoned its plan to gain FDA approval for Glybera after the U.S. regulator told the company it would need to see data from two clinical trials of its drug before it could make a final decision.

- check out GSK's release

- read the CHMP's decision