|

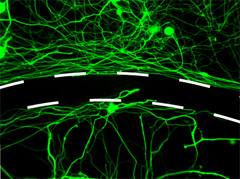

| Scientists have created a drug that helps nerve fibers cross scar tissue barriers after spinal cord injury.--Courtesy of NIH |

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine have taken an end-around approach to treating spinal cord injuries, crafting a treatment that has shown the promise of reversing paralysis in early studies.

As the scientists explain, damage to the spine often severs long nerve fibers called axons, interrupting brain signals and leading to paralysis. During the healing process, axons try to traverse the damaged area and reconnect with their counterparts but, due to the interaction between an enzyme called PTP sigma and class of proteins expressed in scar tissue, they can't get across.

Examining that impasse, Case Western's Bradley Lang came up with the idea of creating a drug that could block PTP sigma and help fledging axons grow and restore the body's nerve network. And, in a preclinical study published in Nature, the treatment did just that.

With help from the National Institutes of Health, a Case Western team led by professor Jerry Silver tried the subcutaneous drug on rats with paralysis due to injury, finding that the treatment led to marked improvements in their ability to walk and urinate. Examining the rats in the treatment group, Silver's team noted that their drug spurred rampant axon growth below the site of injury, lending weight to the guiding hypothesis and lighting the way for future study.

It's extremely early days for Case Western's treatment, of course, and recent scientific history is littered with agents that show exhilarating promise in animals only to fail quietly on further examination. That said, there are no available drugs to help spinal cord injuries heal, and many in-development treatments are stem cell therapies, requiring invasive procedures that could further damage tissues on the mend. Case Western's candidate, by contrast, can be injected underneath the skin.

"We're very excited at the possibility that millions of people could, one day, regain movements lost during spinal cord injuries," Silver said in a statement. "... We now have an agent that may work alone or in combination with other treatments to improve the lives of many."

- read the study

- check out NIH's statement